When I talk about my new book, people often ask what one thing surprised me most about my travels in the world I call the Land of Ballet. What always comes to mind is a single word: generosity.

As a ballet outsider, most of what I thought I knew about the ballet life offstage came from movies and writings that emphasize ballet’s competitiveness, with the adjective “cutthroat” in there somewhere. Not to say that aspect of ballet doesn’t exist, but though it may make for good drama, it’s not the real story.

Again and again among dancers and teachers, I saw examples of generosity that were not simply random, but intrinsic to this world. The real-life counterparts of the ballet teacher who nurtures Billy Elliot and his talent turn out not to be the exceptions but the rule. The die-for-your-art histrionics of The Black Swan and The Red Shoes mercifully exist mostly in the realm of fiction.

If you Google “ballet generosity” you’ll find plenty of hits, mostly mentions of donors’ gifts, with a few citations for The Sleeping Beauty ballet’s “Fairy of Generosity.” They’re important, but the generosity I saw and heard was a different caliber, the moving personal bigheartedness we’re all supposed to think about at holiday time and practice all year round but seldom do.

It’s different in the Land of Ballet. During rehearsals of Balanchine’s Prodigal Son early in my stay at Pacific Northwest Ballet, veteran principal dancer Ariana Lallone shared tips on dancing the Siren with then-corps-member Lindsi Dec, who was tackling the role for the first time. This wasn’t unusual: Those with more experience in roles repeatedly helped those who were new to them, typically their juniors in rank. The most touching example among many I saw was when injured principal dancer Carla Körbes came in to the studio despite an aching back to coach a potential replacement for her lead role in Roméo et Juliette.

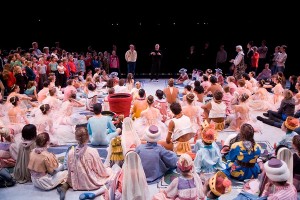

Again and again, I saw dancers work through their precious union-mandated hourly break to help out their colleagues or time-pressed stagers and choreographers. Again and again I saw stagers and choreographers and instructors use encouragement rather than disparagement to get their messages through. Though the tough-looking shaven-headed Jean-Christophe Maillot, artistic director of Ballets de Monte-Carlo and choreographer of that Roméo et Juliette, occasionally barked out commands during the heat of rehearsals, he more often prefaced his corrections with the generous phrase, “I think it’s nice if . . .” as a way of softening what could just as well have begun “Do this!” Later, Maillot would say that PNB’s dancers “gave me a lot. There was a real generous feel, a real hunger from them to get something.” Those choreographers who scream, “You mahst geev me more . . . passion!” exist mostly in movieland.

I saw dancers give up vacation time to perfect a benefit performance for victims of Hurricane Katrina two thousand miles away. I saw dancers come in to the studio on their days off to convey their wisdom and experience to students rehearsing a piece the veterans had performed in the past. I saw a principal ballerina spend her lunch hour coaching a young dancer in the fine points of a competition solo. I heard from a PNB teacher how an injured colleague stood in the wings to make sure his understudy—that teacher, back in the day—would succeed in a role he’d been thrust into literally overnight.

I heard dancer after dancer express gratitude for the endlessly generous ballet moms and dads whose time and money got them to and through their dance studies. I saw older students take the time to act as role models graciously answering little novices’ questions. I watched dancers applaud their colleagues in the studio and congratulate them on Facebook. They didn’t have to; they just did.

Generosity simply goes with the territory, in part for reasons that have do to with the team nature of ballet companies and schools and the way dances are handed down through time and space. At a faculty meeting, Peter Boal told colleagues that he asks student dancers to be generous in working with partners, remembering that for a time at the School of American Ballet, the only girl who would dance with him by choice “was five-nine when I was five-four.” That generous soul was Deborah Wingert, who like Boal went on to dance with New York City Ballet.

Back to Prodigal Son again. Like most work in the canon, it’s handed down from body to body, mind to mind. Back in the 1980s, nineteen-year-old Peter Boal was cast in the title role for the first time. “Balanchine had just died, and nobody knew what the coaching was like.” Boal found tapes of Balanchine coaching Baryshnikov in the role, but “sometimes they break into Russian.” Boal wanted to work with Edward Villella, so famous for the role that he titled his autobiography Prodigal Son, but Peter Martins, the new head of City Ballet, wouldn’t go for it. So Boal “hired Villella to coach me. I said, ‘I’ll pay you.’

“He said, ‘I cost one beer.’”

For the holiday season and beyond, I wish you a passel of friends and colleagues as generous as the ones who inhabit the Land of Ballet.

posted November 29, 2011